By kind permission of Roger Nicholas.

Arthur Onslow was born on 1 October 1691 in Kensington, the son of Foote Onslow and nephew of Richard Onslow who was subsequently a speaker of the House of Commons (1708-1710). He was also the great grandson of Sir Richard Onslow the purchaser of Clandon Park in 1641.

The young Arthur was said to be melancholy, diffident and lacking ambition, and he is credited with the adoption of ‘Festina Lente’ as the sole motto of the Onslow family (which might be said to reflect his personality) to replace that with which it was also earlier used, ‘Semper Fidelis’. On the credit side, he was dignified, lacking in pomposity and he inherited his mother’s family’s good looks.

Arthur was educated at Guildford Royal Grammar School and Winchester College and matriculated at Wadham College, Oxford, in 1708 but did not take a degree. He was subsequently called to the bar at the Middle temple in 1713, making little progress as a lawyer, but he became a bencher of the Inner temple in1728. By 1737 he was recorder of Guildford and high steward of Kingston.

Onslow was not a wealthy man so his financial circumstances were significantly improved when in 1720 he married an heiress, Anne Bridges, of Thames Ditton. At this time he acquired Levyl’s Grove (later Levylsdene) at Merrow but subsequently took up residence at Imber Court, part of his wife’s inheritance. The issue from the marriage was George, the first earl of Onslow, (1731-1814) and Anne who died unmarried in 1751.

In his teens he had spent holidays at Clandon with his uncle, Richard, and it was he who implanted the idea of a career of public service in Arthur’s mind. In 1715 when his uncle was Chancellor of the Exchequer he accepted from him the post of private secretary, and he later moved on to the Post Office, both of these appointments providing him with character-build experience. By 1720, Onslow’s inclinations had turned towards politics and in February of that year he was returned to the Commons as a Whig MP for the borough of Guildford which he continued to represent until 1727. During this period, his profile as a back-bencher seems to have been on the low side as he is reported to have spoken in the House on only three occasions. Perhaps therein lay the seeds of success for his future parliamentary career.

During the general election of 1727 he was returned for the constituencies of both Guildford and Surrey. He opted to represent the latter which he continued to do until his retirement in 1761. When the new parliament opened in January 1728 he was unanimously elected speaker, thus becoming the third member of his family to hold this office, the first having been Richard Onslow Esq who died in 1571. He continued to be unanimously re-elected in the years 1735, 1741, 1747 and 1754 thus his term of office as speaker covered the entire reign of George II. Later in 1728 he became a privy councillor and the following year was appointed chancellor and keeper of the great seal to Queen Caroline (who was godmother to his son).

In a previous age of corruption, Onslow was said to have been a man of rare and outstanding integrity. There was to an extent a dichotomy in the performance of his duties. On the one hand his was the first speaker to see the necessity of adopting an aloof approach to the accepted – and questionable – norms of the day regarding members’ behaviour as well as exerting his authority and independence in the House: it is said that he had ‘insoluble gravity of demeanour and a stern refusal to be relaxed or intimidated by wit or dispute’. On the other hand he was by no means detached from the party associations and frequently spoke and voted in committee, attended party meetings and maintained a close friendship with the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole. However, he could be outspoken against the government when its actions ran contrary to his views, two cases in point being the Regency Act of 1751 passed following the death of Frederick, Prince of Wales, and Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753 which formalized the mechanics of the marriage process.

Doubtless his earlier legal training stood him in good stead for he was a stickler for maintaining the procedures and discipline of the house, bullying ministers and intriguing factions receiving equally short shrift. He did much to codify the practices of the day, and no procedural detail was too insignificant for him to enforce. He was very protective of the dignity of the office that he occupied and insisted that due deference be shown to him by members entering and leaving the chamber.

He was at one time most concerned about the question of reporting parliamentary debates, which then constituted a breach of privilege. During 1738 Onslow brought the matter to the attention of the house and a subsequent debate resulted in a resolution condemning the practice. However, in 1742, at his instigation the house ordered its journals to be printed for the first time.

Although he had been appointed to the well paid post of treasurer of the navy in 1734, some eight years later when his was the casting vote on a contentious issue he resigned the following day lest it be thought that his vote might have been influenced by personal gain. Thereafter his income was reduced to his salary as speaker which included the fees from private bills.

Eventually, Onslow’s health deteriorated and he resigned in 1761. His parliamentary colleagues petitioned the king to be ‘graciously pleased to confer some signal mark of his royal favour’ upon the retiring speaker. In response, the king granted an annuity of £3,000 for the lives of both Arthur and his son George, the first time that a retiring speaker had been awarded a pension. Other honours followed including the freedom of the City of London and election as a trustee of the British Museum.

Arthur Onslow died on 17 February 1768 at his home in Great Russell Street, London, aged seventy-six. He was initially buried at Thames Ditton with his wife who had died five years earlier, but both were later re-interred in the burial-place of the Onslow family in St John’s Church, Merrow.

Between 1698 and the present day there have been thirty-four speakers of the House of Commons which represents an average incumbency in the office of just less than nine years, putting into sharp focus Onslow’s achievement of thirty-three years. His closest contender, Charles Shaw-Lefevre, completed eighteen years between 1839 and 1857 (that is, from Queen Victoria’s early reign until the Indian mutiny). The other speaker with Guildford connections was, of course, Bernard (later Lord) Weatherill (1983-92) who died in 2007.

There can be no doubt that Onslow possessed qualities of honesty and rectitude which acted as a beacon in an age when standards in public life were at a particularly low ebb.

The words that he penned in 1740 to Sir More Molyneux of Loseley have a resonance nearly two hundred and seventy years later:

‘God knows there is so much of it (corruption) about everywhere that I dread the consequences of it with regard to the religion and morals of the nation, and to tell you the truth I am quite sick of the world’.

Acknowledgements: The Onslow Family – C E Vulliamy

The Royal Grammar School, Guildford – D M Sturley

The Dictionary of National Biography

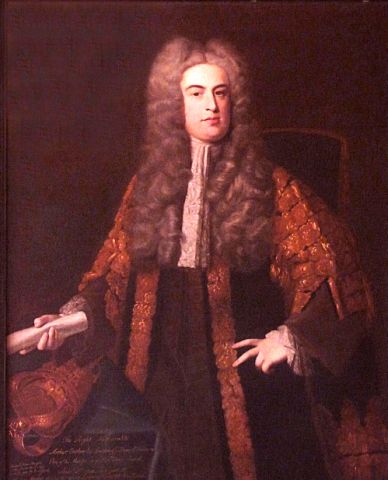

The portrait of Arthur Onslow in Guildford Guildhall.